Vote for Vellum! The 'roll' [sic] of parchment and vellum in preserving history and heritage

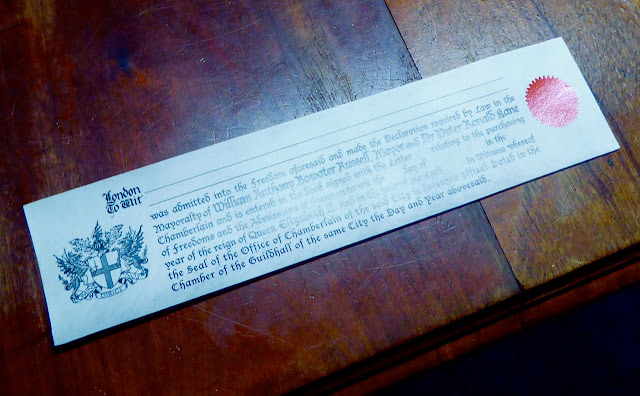

Most Freemen choose to have their Copy of Freedom (as it is described) framed by the Chamberlain's Court before they leave Guildhall. Because of this the Freemen rarely, if ever, handle the document to feel its texture, perhaps they assume it's just a piece of paper.

Every Copy of Freedom is written on fine quality parchment rather than paper. The parchment is made from the skin of a sheep and is produced in the UK by William Cowley of Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire (a family owned business founded in 1850).

The College of Arms in the City of London is another major user of vellum and has been for centuries. Grants of arms are still presented on vellum today and are richly illustrated, making a treasure that will, like a coat of arms, be unique and perpetual. Likewise the Court of Lord Lyon in Edinburgh and the Canadian Heraldic Authority make use of William Cowley's products.

When the parchment or vellum has been reduced to the required thickness it is marked with the maker's mark and is then ready for cutting, dying (if required) and storage. The highest quality vellum is covered with a glue made of the offcuts of the skin to give it an even smoother surface. This particular style of vellum is known as kelmscott and is used for the very finest illustrations that can achieve a precision and level of detail that is impossible to deliver on paper.

Some goatskin vellum is dyed for use in the production of interior furnishings. A wide range of colours are possible and the pattern achieved will be unique to each skin as the oil in the skin will cause the dye to be absorbed in differing strengths.

Another characteristic of the unique nature of parchment and vellum is that it contains DNA. This enables the artist to keep a small section of the material for future testing against any suspected fake or forgery. While it is possible to copy brush and pen strokes, to source ages canvas, to use 3D printing and other techniques to defeat the art dealer and specialist, DNA cannot be forged. Using vellum or parchment as the medium for painting and illustration allows the artist, the dealer, the auctioneer and the owner to prove beyond all doubt the provenance of the work.

A vote for vellum!

Since parliamentary records began in the UK they have been recorded on animal skins. It's for this reason that the events of great importance in our national history are so well recorded. The entry of Charles I into the House of Commons is recorded up to the point that he ordered the scribe to stop writing... just a few years later the scribe had plenty to write during Charles's trial and subsequent execution.

A blow to the craft occurred in 2016 when, after considerable debate, a motion to do away with vellum as a means of recording laws in the UK was debated in the House of Commons. The motion was motivated by short-sighted penny pinching. Thankfully the House of Commons voted it down, however the House of Lords decided to change to using paper none-the-less.

In the end the cabinet office stumped up the funds to achieve a partial retention of animal skin in recording our laws by providing a cover piece in vellum while the content is printed on archive quality paper. The saving to the tax payer was in the order of £10,000-£20,000 per annum, a saving that was immediately wiped out by the cost of maintaining paper in special conditions to slow its inevitable deterioration.

Meanwhile the annual catering and retail service bill for the House of Lords for the year 2017-2018 was £1,346,000.

What's the future for parchment and vellum making?

William Cowley is the only commercial maker of parchment and vellum. The business has a Master and an Apprentice in training along with two other members of staff. The skills take at least seven years to learn in order to become proficient and many more to become a master craftsman. Many of the skills cannot be recorded and transferred in written form as they involve the senses of smell, touch, sound and sight. Above all the craft is one that relies on practical experience and it is therefore vital that the skills are retained by putting them in to practice.

Here I see a role for the Livery Companies, long custodians of ancient crafts, and several have connections with the trade. If the Skinners' Company was on the lookout to re-establish an occupational link, and sponsor an apprentice, what better than sustaining and developing the skills and promoting the work of the vellum and parchment maker?

Every Copy of Freedom is written on fine quality parchment rather than paper. The parchment is made from the skin of a sheep and is produced in the UK by William Cowley of Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire (a family owned business founded in 1850).

William Cowley is thought to be the last commercial parchment (sheep) and vellum (calf or goat skin) maker in the world, and still crafts with traditional tools and techniques to produce the highest quality materials for writing, drawing, painting and upholstery.

William Cowley's products are used by governments, universities, archive bodies, painters, calligraphers, book binders, interior designers and others who produce documents, paintings, illustrations and anything that might otherwise be represented and stored on paper. If you want to ensure a written document is around in 1,000 years - vellum or parchment is the best and perhaps only choice.

The City of London's connection with parchment and vellum is also evident in the numerous Royal Charters granted to the Livery Companies, the Letters Patent granting arms to individual Liverymen and to their respective Livery Company, and in the Royal Warrants that appoint the City's Sheriffs (on display in the Old Bailey).

|

| Detail from the Letters Patent granting arms to the Drapers' Company, dating from the mid 15th century |

The College of Arms in the City of London is another major user of vellum and has been for centuries. Grants of arms are still presented on vellum today and are richly illustrated, making a treasure that will, like a coat of arms, be unique and perpetual. Likewise the Court of Lord Lyon in Edinburgh and the Canadian Heraldic Authority make use of William Cowley's products.

So why do we still use parchment and vellum in the 21st century?

Parchment and vellum are exceptionally strong, hard wearing, long-lasting and stable products that will last for many centuries, even millennia under normal storage conditions. They are sustainable, organic products that are environmentally friendly and exceptionally versatile.

If you are in any doubt about the qualities of animal skin as superior product to paper, ask yourself this question: Why don't we make shoes out of paper? Mudlarks are still finding Roman era leather shoes on the banks of the Thames at low tide anywhere up to 2,000 years after the Roman's arrived in London. Think about that for a moment: Those shoes have survived 2,000 immersed in river water!

Parchment and vellum provide a superior product for all manner of documents that will have a lifespan of many centuries. They do not require any special storage requirements and may be displayed or stored in the home or workplace.

How important is parchment and vellum in the history of written communication?

No copy of Magna Carta would exist today had that document been written on paper. Tony Hancock would never have said those immortal words 'Does Magna Carta mean nothing to you, did she die in vain?'.

The Liber Albus or White Book of the City of London, the oldest book on Common Law, would not exist had it been written on paper. The Domesday Book would be unknown to us had it been a paper manuscript. The various Mappa Mundi would be unknown to us although I'm sure Sir Terry Prachett's Discworld makes for a suitable 21st century alternative.

The Liber Albus or White Book of the City of London, the oldest book on Common Law, would not exist had it been written on paper. The Domesday Book would be unknown to us had it been a paper manuscript. The various Mappa Mundi would be unknown to us although I'm sure Sir Terry Prachett's Discworld makes for a suitable 21st century alternative.

With the exception of stone carving, our written knowledge of early history, the development of religion, government, law, politics and other pivotal events in the growth of civilisation would be entirely gone. Events leading to and following the Norman Conquest would be known only by a large embroidery (erroneously described as a tapestry) in Bayeux, and so on throughout history.

The importance of parchment and vellum to the development of civilisation cannot be over-emphasised. Simply put without it our history would be gone.

Surely paper can replace animal skins?

Modern paper manufacturing processes rely on wood pulp which becomes acidic over time even if Ph neutral or alkaline at the time of manufacture. This causes it to break down in as little as a week after manufacture in normal conditions. Paper also suffers from photo-degradation and of course it doesn't get on well with water, and burns rather enthusiastically.

Archiving of written records on paper requires specialist paper designed to counteract the development of acids, specialist inks and careful handling (our hands transfer oils to the paper which accelerate the degeneration) and lastly specialist storage conditions. In short if you plan to archive on paper you have to manage the inevitable degradation from which paper suffers.

From the perspective of animal welfare not a single calf, sheep or goat would be saved or have a longer life by ceasing to use parchment or vellum as supply far outstrips demand. Most animal carcasses go to landfill, parchment and vellum making takes a minuscule proportion of the world's existing trade in animal products, taking only what would otherwise be destroyed.

Conversely paper is a manmade product that comes from wood pulp, not always from sustainable sources, and often forested from mono-crop forestry plantations that have their own environmental challenges. A 2018 report into the state of the global paper industry by the Environmental Paper Network states that 'Paper consumption is at unsustainable levels and globally is steadily increasing... the industry has substantial climate change impacts'.

Despite all the hopes of a paperless office resulting from the advent of computers, global paper consumption continues to increase to an average of 55kg per person per year with attendant issues of water pollution, consumption of fossil fuels, greenhouse gas emissions and a consequential growth in government regulation of the industry. Who among us does not have a recycling bin for paper as a result of legislation to lessen the environmental impact?

Animal skins are a natural product and nature creates no waste. That said intensive farming methods of livestock also brings environmental challenges, but overall parchment and vellum are environmentally superior to paper in every respect.

Another benefit of parchment and vellum is that it is reusable. Manuscripts can be cleaned and smoothed down with pumice stone to produce a fine surface that may be written on again. With the use of UV technology it is possible to read the original text. Manuscripts of this type are called palimpsests.

Another benefit of parchment and vellum is that it is reusable. Manuscripts can be cleaned and smoothed down with pumice stone to produce a fine surface that may be written on again. With the use of UV technology it is possible to read the original text. Manuscripts of this type are called palimpsests.

Making of parchment and vellum

In November of 2019 I had the privilege of visiting William Cowley to see, smell, hear and feel the process of parchment and vellum making. I'm indebted to Paul Wright, General Manager of William Cowley for allowing me to visit as the firm is not normally open to visitors.

The process starts with selecting animal skins from an abattoir, and this needs to be done before they begin to rot. A tiny proportion of animal skins are selected and while 500 may be examined in a day, perhaps 60 are taken. The end to end process takes about six weeks so the total number of skins taken by William Cowley is impossibly small to measure against the scale of the meat industry world-wide.

Since skins are organic products, the concepts of industrialisation and uniformity of production are alien to parchment and vellum making. Just as no two humans are the same, no two animals are the same. Factors such as species, age, diet, season, exposure to the elements, pigmentation and even whether the animal died naturally or was slaughtered will all affect the skin.

The skins are stored 'salted' (another natural substance) until they are ready to be washed in lime over several day which aids the removal of hair. Eventually the skins are clean enough to be dried and stretched on a frame called a hearse. Drying is achieved through the natural circulation of air in a warm room, no direct heat is applied and the skins dry quickly as they would if the animal were skill alive.

|

| The beast that once had this skin is now 'pegged out', the frame on which it is held under tension while drying is aptly named a hearse. |

Once the skins are dried they are held under tension and scraped with a tool named a lunar or lunarium which is a curved blade with a double handle. The skin is scraped with a punching motion which removes any remaining hair and pigmentation on the upper side, and the sinews of fat on the underside. I had a go at using the lunar and found that it wasn't necessary to apply any great pressure to work the surface of the skin, but parchment making career was very short so if you want to see the Master and Apprentice in action, watch this short video.

|

| Cleaning a sheep skin to make parchment. The curved blade, called a lunar(ium) acts somewhat like a razor to achieve a smooth surface. |

When the parchment or vellum has been reduced to the required thickness it is marked with the maker's mark and is then ready for cutting, dying (if required) and storage. The highest quality vellum is covered with a glue made of the offcuts of the skin to give it an even smoother surface. This particular style of vellum is known as kelmscott and is used for the very finest illustrations that can achieve a precision and level of detail that is impossible to deliver on paper.

|

| Every finished skin is marked with the maker's personal mark for quality control and traceability |

Some goatskin vellum is dyed for use in the production of interior furnishings. A wide range of colours are possible and the pattern achieved will be unique to each skin as the oil in the skin will cause the dye to be absorbed in differing strengths.

Another characteristic of the unique nature of parchment and vellum is that it contains DNA. This enables the artist to keep a small section of the material for future testing against any suspected fake or forgery. While it is possible to copy brush and pen strokes, to source ages canvas, to use 3D printing and other techniques to defeat the art dealer and specialist, DNA cannot be forged. Using vellum or parchment as the medium for painting and illustration allows the artist, the dealer, the auctioneer and the owner to prove beyond all doubt the provenance of the work.

|

| Dyed vellum is used in the luxury furniture trade and is exceptionally hard wearing. |

|

| Every piece of dyed vellum will exhibit a differing pattern which results in every piece of furniture that uses vellum being a unique artefact which is special to the owner. |

A vote for vellum!

Since parliamentary records began in the UK they have been recorded on animal skins. It's for this reason that the events of great importance in our national history are so well recorded. The entry of Charles I into the House of Commons is recorded up to the point that he ordered the scribe to stop writing... just a few years later the scribe had plenty to write during Charles's trial and subsequent execution.

A blow to the craft occurred in 2016 when, after considerable debate, a motion to do away with vellum as a means of recording laws in the UK was debated in the House of Commons. The motion was motivated by short-sighted penny pinching. Thankfully the House of Commons voted it down, however the House of Lords decided to change to using paper none-the-less.

In the end the cabinet office stumped up the funds to achieve a partial retention of animal skin in recording our laws by providing a cover piece in vellum while the content is printed on archive quality paper. The saving to the tax payer was in the order of £10,000-£20,000 per annum, a saving that was immediately wiped out by the cost of maintaining paper in special conditions to slow its inevitable deterioration.

Meanwhile the annual catering and retail service bill for the House of Lords for the year 2017-2018 was £1,346,000.

What's the future for parchment and vellum making?

William Cowley is the only commercial maker of parchment and vellum. The business has a Master and an Apprentice in training along with two other members of staff. The skills take at least seven years to learn in order to become proficient and many more to become a master craftsman. Many of the skills cannot be recorded and transferred in written form as they involve the senses of smell, touch, sound and sight. Above all the craft is one that relies on practical experience and it is therefore vital that the skills are retained by putting them in to practice.

Here I see a role for the Livery Companies, long custodians of ancient crafts, and several have connections with the trade. If the Skinners' Company was on the lookout to re-establish an occupational link, and sponsor an apprentice, what better than sustaining and developing the skills and promoting the work of the vellum and parchment maker?

Want to learn more about the Livery Companies and the City of London?

The City of London Freeman's Guide is the definitive concise guide to the City of London and its ancient and modern Livery Companies, their customs, traditions, officers, events and landmarks. Available in full colour hardback and eBook formats and now in its fifth or Platinum Jubilee edition. The guide is available online from Apple (as an eBook), Amazon (in hardback or eBook) Payhip (in ePub format) or Etsy (in hardback or hardback with the author's seal attached). Also available from all major City of London tourist outlets and bookstores. Bulk purchase enquiries are welcome from Livery Companies, Guilds, Ward Clubs and other City institutions and businesses.

The City of London Freeman's Guide is the definitive concise guide to the City of London and its ancient and modern Livery Companies, their customs, traditions, officers, events and landmarks. Available in full colour hardback and eBook formats and now in its fifth or Platinum Jubilee edition. The guide is available online from Apple (as an eBook), Amazon (in hardback or eBook) Payhip (in ePub format) or Etsy (in hardback or hardback with the author's seal attached). Also available from all major City of London tourist outlets and bookstores. Bulk purchase enquiries are welcome from Livery Companies, Guilds, Ward Clubs and other City institutions and businesses.

|

| The City of London Freeman's Guide, 6th or Sovereign's edition |

I welcome polite feedback and constructive comment on all my blog articles. If you spot and error or omission, please do let me know (please illustrate with verifiable facts linked to an authoritative source where appropriate).

I ask that all persons who wish to comment take the time to register as I receive copious spam and postings from crackpot conspiracy nuts which would otherwise overwhelm my blog with rubbish and nonsense.

I ask that all persons who wish to comment take the time to register as I receive copious spam and postings from crackpot conspiracy nuts which would otherwise overwhelm my blog with rubbish and nonsense.

Comments

Post a Comment